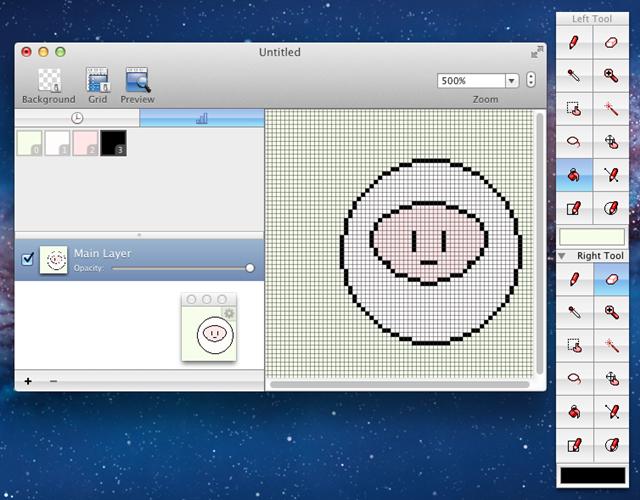

Hence the rise of “pixel art.” Simply Google the term and you’ll find the trend Whatever the motivation, there has been a huge interest in creating art and graphics that return to that blocky, bright-colored, low-fi look of early video games. While this is largely irony-driven, the nostalgia of first-generation gamers who are now reaching adulthood is sincere. However, a glance into any Urban Outfitters will reveal, through racks of Transformers T-shirts and cassette-tape belt buckles, our youth culture’s obsession with appropriating the aesthetic of the 70’s, 80’s, and early 90’s. The rapid advances in computing speed and memory capacity in the past 30 years are all that separate the generations. The difference is the number of pixels in each image (resolution) and the number of colors each pixel can be tuned to (color depth). He, in contrast, is 389 pixels high and is modeled in the 16,777,216 colors of 32-bit graphics.* Both images are essentially the same: a grid of pixels tuned to specific color values.

Next to him is a direct descendent from nearly 30 years in the future, a creature from 2007’s Halo 3. The left character hails from 1978’s Space Invaders, is 10 pixels high, and is rendered in 1-bit color (each pixel is either ‘on’ or ‘off’). These are both screenshots of video game aliens. In these simplified low-resolution images, the pixels, small grid squares of color that make up all digital images, were still quite visible: Images and gaming environments were simplified by limiting the color palette, resolution, interactivity, and level of detail.

Pixen for windows software#

These early computer games (and any other software that required graphics) did not have access to nearly as much computing power as we do today. Enter: Isometric projections! The classic SimCity is a great example of this: This brings us to one of the prominent uses of isometric projection in our culture: computer game graphics.īefore the dawn of complex 3D physics engines, early low-power gaming systems needed to represent 3D environments in a simple, yet passably realistic manner. This association is so strong that our minds actually read real photographs of isometry as some sort of replica or computer graphic. The artificial, toy-like “computer-gamey” feel is due purely to our cultural associations of isometric projections with artificial illustrations. This is not an illustration, and the photograph has not been altered in anyway.

Knowing this, a photographer may actually place him/herself at this exact location in relation to the subject, and replicate isometry through photography, as in this real photograph of a corner in NYC: Escher’s famous illusions were achieved through the juxtaposition of placing an isometric object against a non-isometric background.īecause isometry is built around a very specific set of angles, it actually represents the view from a precise camera angle above and in front of the object. This illusion is only possible due to the equally foreshortened axes of an isometric projection.

However, because all axes meet at equal angles, isometry is often easier to draw and also allows for interesting illustrative possibilities, including optical illusions like one found on this Swedish postage stamp: See these three different projections of the same desk: In fact, non-isometric renderings often look more natural to many viewers as they cause less distortion to the “front” face of an object. It is quite common to represent 3D objects using projections in which these angles are not equal. When the axes of height, width, and depth meet, the angles formed are all equal (120 degrees), like so:Īll this is in the word: iso meaning “equal” and metric meaning “measurement”. Isometric Projection is special because every dimension is equally foreshortened. In fact, even if you draw just a square to represent a cube, you’re still using Orthographic Projection, which repesresents just one side of a 3D object at a time. Every time you draw a cube as something more than just a square on your page, you’re using a form of projection. A projection is simply a method of representing a 3D object in 2D space, used everywhere from Renaissance perspective painting to architectural modeling software. “Isometic” is a style of graphical projection. What does this mean? Let’s break it down! But here we go with a little something the gra phic designer/illustrator in me thinks is really neat. Neither of these is conducive to getting a blog entry done. I seem to go through alternating cycles of being either extremely busy or extremely lazy.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)